Economy & Markets #4 - Geopolitical risk declining, or not?

This week's topics:

Japanese government bonds under further pressure: is there a definitive "Liz Truss moment" coming in Tokyo?

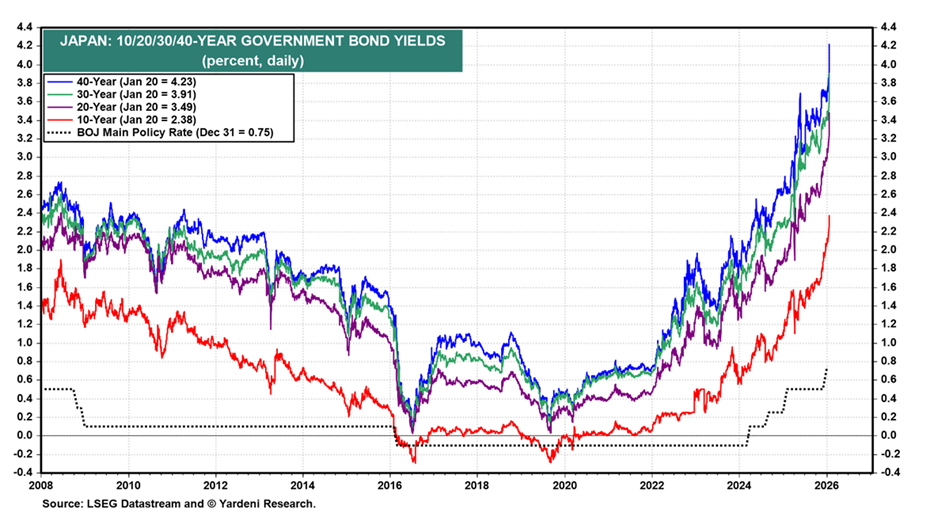

The Japanese government bond market (JGBs) has been remarkably turbulent in recent months. Whereas Japan was for years the epitome of stable (and above all low) interest rates and an economy with deflation (good for bondholders), we are now seeing a clear sell-off, particularly on long maturities. This is not only relevant for Japan itself, but also for global markets via the well-known JPY carry trade. In this trade, not only Japanese private individuals (the well-known "Mrs. Watanabe"), but also hedge funds and banks borrow at low Japanese interest rates to reinvest in (high-yielding) assets in the US, Europe, and Australia. Given the size of the JPY carry trade, with BIS data based on FX derivatives pointing to a yen supply of approximately $1.3–1.7 trillion, an increase in JPY financing costs could cause global turmoil as investors reduce their JPY carry positions and repatriate capital.

What exactly is going on?

The period of deflation from the late 1990s to the mid-2010s was the result of several factors: the bursting of the Japanese real estate bubble (it is said that the land under the Imperial Palace was once more expensive than all the real estate in Florida combined), an aging population (deflation is favorable for savings and pension income), and a strong yen. This period allowed the Japanese central bank to keep short-term interest rates very low for a long time. After decades of deflation, Japan now suddenly finds itself in an uncomfortable mix of persistent inflation and still low short-term interest rates. Due to the weak yen, inflation is being imported, as it were, through energy bills (like China, Japan has relatively few natural resources) and higher prices for imported goods (such as rice). With inflation at roughly 3% and short-term interest rates at around 0.75%, real interest rates are clearly negative. Under normal circumstances, this is almost "policy-wise ideal" for a government that wants to inflate away its (high) national debt. But these negative real interest rates only work as long as investors believe that:

- inflation will eventually come under control again, and

- the yen does not continue to weaken structurally.

As soon as that confidence falters, investors demand higher returns on long-term bonds. And that is exactly what is happening now. Whereas long-term interest rates in Japan were still around 0.6% in 2020, they have risen rapidly to 4.3%. This implies substantial losses, roughly in the order of tens of percent for long-term loans, and is reminiscent of the performance of ultra-long Austrian government bonds in terms of volatility. The big difference, however, is that in Japan the risks lie in the public sector (the Bank of Japan has already bought up 55% of the government debt), while in the case of Austrian bonds, the risks lie mainly with European insurers and pension funds.

Japan is known for its exceptionally high public debt (more than 260% of GDP (IMF)). At the same time, the government holds substantial financial assets and a large portion of the debt is held domestically. As a result, the net debt (150% MOF and 78%, estimate by St Louis Fed) is less dramatic than the gross figures suggest. The key question for investors is therefore not "can Japan pay?", but rather: will the combination of inflation, policy and yen stability remain credible? Not because Japan is identical to the UK, but because the mechanism could turn out to be similar. As soon as investors start to doubt the fiscal course or the role of policy as an anchor, the risk premium rises and interest rates can rise sharply in a short period of time. For Japan, where stability has been the norm for decades, this would be a clear regime shift. High inflation also normally spells the end of the government. Japan is not an isolated market. A shock in JGBs can spread to other markets through multiple channels:

- Searching for the next weak link in (unsustainable) sovereign debt: how long can countries such as Belgium, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal continue to finance their sovereign debt on their own?

- Interest rate differentials: higher Japanese interest rates change global relative valuations.

- Exchange rates: movements in the yen directly affect international portfolios.

- Positioning and leverage: in times of stress, positions are not "reconsidered" but often quickly reduced.

Budgetary pressure and politics increase the risk premium

The risk premium may rise further as government deficits increase again. Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi is pursuing a more assertive international policy, with elements reminiscent of a Japanese “chips act” for industry. At the same time, tensions with China are rising, which could lead to higher defense spending. And, of course, higher interest rates also mean a greater burden of interest charges on the budget. Prime Minister Takaichi unexpectedly dissolved parliament this week and called an early election for February 8. Her campaign includes a proposal to suspend the 8% consumption tax on food for two years (order of magnitude ~¥5 trillion), which is causing concern among investors about additional spending and fiscal discipline.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Super investor Ken Griffin critical of European politicians: Just do it!

Ken Griffin is the founder and CEO of Citadel (hedge fund) and owner of Citadel Securities (market maker). His fortune is estimated by Forbes at approximately USD 51.8 billion. Griffin, who is known to be Republican-leaning, called for more decisive action in Europe at Davos: less talk and faster reform, particularly to strengthen growth and competitiveness. At the same time, he is critical of the debt dynamics in countries such as Japan and France. He is relatively more positive about the US: in his view, the US economy remains resilient; the BEA reported real GDP growth of 4.4% (annual rate) for Q3 2025, while the GDPNow (Atlanta Fed) forecast for Q4 2025 was around 5.4% (as of January 21, 2026). His main warning to Washington: do not undermine the independence of the Federal Reserve, as political pressure on monetary policy increases the risk of new inflation shocks, according to Griffin.

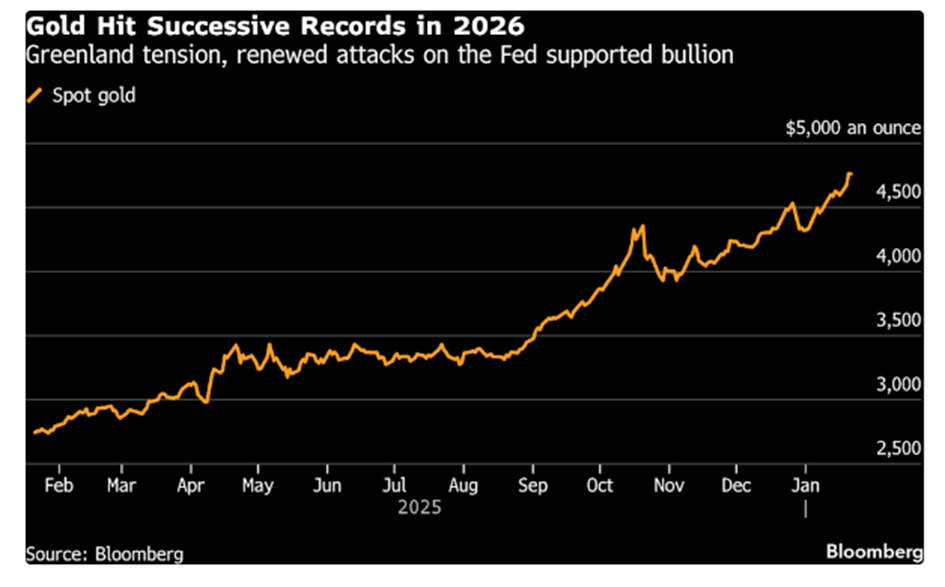

Ray Dalio in Davos: monetary order under pressure, more "money printing" and flight to hard assets such as gold

In his book "How countries go broke," super investor Ray Dalio (founder of hedge fund Bridgewater) warns that rising debt increases pressure on central banks to "prop up" the system with extra liquidity, with the risk of currency weakening and new waves of inflation. Developments in Japan are not unique in this regard: in this new regime, Dalio seeks protection in gold and other hard assets and advises steering clear of government bonds. He also looks at gold and defense-related investments, appropriate in a world where geopolitical tensions are structurally higher. He previously explicitly mentioned gold as a hedge/'reserve asset' for this new regime, with a guideline of 5-15% in gold in a well-diversified portfolio. His view is supported by Goldman Sachs analysts, who even see the price of gold rising to USD 5,400 per troy ounce (versus USD 4,900 per ounce now).

We emphasize that the combination of rising geopolitical tensions and exceptionally high government debt (Japan, Europe, and the United States) is increasing demand for "safe havens." This partly explains why precious metals have been the focus of sustained interest in recent times.

Gold miners: long gold - short oil

Last year, we already pointed out the attractiveness of gold miners in our (model) portfolios. Miners not only benefit from rising gold prices, but in many cases also from lower (or falling) energy prices, particularly for fossil fuels. After all, metal extraction is very energy-intensive, partly because ores are found in increasingly lower concentrations on average. This means that more rock has to be moved, ground, and processed to obtain the same amount of metal, resulting in rising energy demand per unit produced.

This is particularly true for copper, which plays an important role in the energy transition. Very rough calculations conclude that the production of 1 ton of copper consumes more than 4,000-7,000 liters of diesel (with large variations depending on the ore, mining method, and process route). For gold, this figure is unimaginably higher: the same calculations lead to extreme estimates of up to 7,000-18,000 liters of diesel consumption for the production of 1 kilogram of gold. The chart below shows that the gold price–oil ratio has sometimes reached extreme levels in the past. The previous peak occurred when oil briefly traded at negative prices during the coronavirus pandemic. The current ratio, which is once again very high, indicates that gold miners' margins could accelerate further.

DNB's risk glasses: strict on gold and Big Tech, but possibly blind to "safe" long-term debt securities?

The Dutch Central Bank (DNB) has been issuing explicit warnings about the risks associated with gold for years, and more recently also about US Big Tech stocks. This is justifiable from the perspective of limiting concentration risk exposure to momentum stocks, but it raises an uncomfortable question. Precisely because these categories continue to perform well in many cases, while the biggest shock to pension investors in recent years came from a different angle: namely, long-term interest rates and bonds.

DNB itself holds more than 600 tons of gold, worth approximately €49 billion at the end of 2024, and labels this as an "anchor of confidence." At the same time, in 2011, it forced the Pensioenfonds Vereenigde Glasfabrieken pension fund to reduce its gold position from approximately 13% to 1%, because this did not fit within the prudent person approach. Since then, the return on gold has risen by approximately 200% (in euros), while long-term bonds have remained stuck at 0% at best since 2011.

American technology also poses a risk of repetition. DNB warns that at the end of July 2025, pension funds had invested approximately €150 billion in the "Magnificent Seven," almost 43% of their listed equity portfolio. In terms of content, this analysis is defensible, but again, the greatest realized risk lay elsewhere. According to DNB's own figures, total pension assets fell by €406 billion in 2022, largely due to price losses on long-term bonds. This underlines that interest rate hedging does not eliminate risks, but merely shifts them. The coverage ratio may remain stable, while real earning capacity is under pressure.

In our model portfolios, we remain critical of bonds as long as financial repression continues (central banks keeping interest rates lower than inflation, leading to negative real interest rates). There is also a degree of fiscal repression when investing in bonds. Dutch private investors must pay a minimum of 2.2% tax on bonds, while Belgian investors pay 30% Reijnder tax on the capital gains of bond funds.

Incidentally, it appears that another large Dutch pension fund read our advice in last week's newsletter not to invest in US government bonds, either on a hedged or unhedged basis. 😉

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Geopolitical risks are increasing, but not where people think

Stock markets experienced higher volatility this week. Much of this was driven by renewed concerns about a possible resurgence of last year's trade conflict. We are now accustomed to strong statements from Washington, but the markets were still shaken when President Trump threatened military escalation around Greenland and import tariffs of up to 200% on European (particularly French) goods. This shifted attention to his speech in Davos: would it remain rhetoric, or would concrete measures follow?

In Davos, Trump spoke of a "framework" for a future deal with regard to Greenland, in coordination with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte. At the same time, it was reported that previously announced trade measures against a number of European countries had been withdrawn or softened, presented as a gesture of goodwill in a broader negotiating framework. For investors, the emphasis on de-escalation was particularly relevant: "I don't want to use force" fits the familiar pattern of the so-called "TACO trade" ("Trump Always Chickens Out"): sharp rhetoric that ultimately leads to a more pragmatic compromise (and thus an ideal buying opportunity).

Why Greenland remains strategic

Trump's blunt approach is leading to increasing resistance, growing suspicion, and more and more discussions about a multipolar world order. Both Canadian Prime Minister Carney and French President Macron are now openly discussing (exploratory) trade deals between Canada and China and closer cooperation between Europe and China. In doing so, they are positioning themselves more emphatically at a distance from the US, which is hardly surprising given the now disrupted relations.

In light of this (escalation), it is also not unexpected that the Trump administration is reportedly expressing support for an independence referendum in the Canadian province of Alberta. The US could also push for a similar initiative in Greenland. Don't forget that Greenland is the first territory ever to leave the EU. It joined in 1973 via Denmark, despite considerable opposition among the Greenlandic population. After the introduction of self-government in 1979, the island voted by a narrow majority in a 1982 referendum to leave, mainly because of fishing rights, natural resources, and autonomy. Since 1985, Greenland has had the status of an OCT (Overseas Country and Territory) and maintains limited, specific economic ties with the EU.

For the US, the strategic significance lies primarily in geography. Greenland is located between North America and Europe and forms a crucial element in the so-called GIUK gap (Greenland–Iceland–UK), a zone that is important for monitoring Russian submarine activities in the North Atlantic region. Missiles fired from China or Russia toward the US will fly over the North Pole. In a scenario of strategic threat, every extra minute of detection time can be valuable. Within NATO, Greenland is also relevant for air, sea, and logistics operations in the Arctic region, which is receiving increasing strategic attention due to climate change and changing shipping routes.

Raw material wealth with strategic potential

Greenland has significant sources of rare earth metals, such as neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium, which are essential for applications in the energy transition (wind turbines, electric vehicles) and for defense technology. To date, large-scale production has remained limited, partly due to political considerations, licensing procedures, and environmental frameworks. However, the strategic potential is evident: with a more favorable investment climate and greater American involvement, Greenland could become an alternative to China's current dominance in parts of this value chain. Estimates of the scale vary widely and depend on further exploration, but the subject is now high on the geopolitical agenda.

Boiling point approaching in Iran and Syria

While the media focuses on symbolism surrounding Davos and Greenland, hard facts point to an increasing US military presence in the Middle East. The aircraft carrier US Lincoln is rapidly heading towards the Indian Ocean and has turned off its radars/transponders. B2 bombers and tanker aircraft have flown from the US and the UK to Jordan and Diego Garcia (US base in the Indian Ocean), while non-essential ground personnel in Iraq, the Emirates, and Qatar have been withdrawn. This military build-up is similar to the build-up prior to the bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities in 2025. Although the uprising in Iran appears to have been brutally suppressed, the Iran issue has not disappeared from the agenda of the hawks in the US. However, there remains a fear of a power vacuum emerging, as previously seen in Iraq and Libya. Washington considers the risks of regime change to be high and has opted for strategic restraint for the time being. However, the risk of doing nothing is also high, as developments in Syria are currently demonstrating.

Interesting interviews this week in Davos

Jamie Dimon (CEO of JPMorgan Chase) warned in Davos that the social impact of AI is being underestimated. According to him, technology can displace jobs faster than societies can adapt, posing risks to social stability. He emphasized that retraining and policy must keep pace with technological progress.

Jensen Huang (CEO of Nvidia) Huang stated that the world is only at the beginning of the AI cycle. He called the current investments in data centers, chips, and energy "the largest infrastructure rollout ever" and dismissed concerns about an AI bubble. According to Huang, AI is actually creating new demand for labor, especially in construction, energy, and engineering.

Larry Fink (CEO BlackRock) said that AI investments are not a speculative bubble but a strategic necessity. He explicitly placed the development in the context of geopolitical competition and warned that the West will lose ground if it does not invest more quickly and collectively, with China as the main reference point.

German Chancellor Merz stated in Davos that the old world order is crumbling and superpower politics are back: Russia and China are challenging the US and the existing order, with direct consequences for freedom, security, and prosperity. In order to play a role, Europe must increase its competitiveness more quickly and invest heavily in defense and deterrence, supported by alliances "among equals." At the same time, he pointed to structural European weaknesses that are slowing progress: high and volatile energy costs, fragmented policy, excessive and overly complex regulation, slow decision-making, and a lack of scale in industry and capital markets, which means that Europe often formulates ambitions but falls short in terms of implementation and speed.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Would you like more information about our services?

Contact us

Disclaimer:

No rights can be derived from this publication. This is a publication by Tresor Capital. Reproduction of this document, or parts thereof, by third parties is only permitted with written permission and with reference to the source, Tresor Capital.

This publication has been compiled with the utmost care by Tresor Capital. The information is intended in a general sense and is not tailored to your individual situation. The information should therefore expressly not be regarded as advice, an offer or a proposal to purchase or trade investment products and/or purchase investment services, nor as investment advice. The authors, Tresor Capital and/or its employees may hold positions in the securities discussed, either for their own account or for their clients.

You should carefully consider the risks before you start investing. The value of your investments may fluctuate. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. You may lose (part of) your investment. Tresor Capital accepts no liability for any inaccuracies or omissions. This information is for indicative purposes only and is subject to change.

Read the full disclaimer at tresorcapitalnieuws.nl/disclaimer .