Economy & Markets #50 - Playful scenarios for 2026 and a critical look at Private Equity

This week's topics:

Outrageous Predictions for 2026: provocative, not necessarily predictive

Every December, Saxo Bank publishes its annual Outrageous Predictions: a series of thought experiments with a low probability but potentially very high impact. The goal is not to predict the future, but to challenge investors to think outside the consensus.

Where are the white swans and where are the black swans hiding?

These scenarios are explicitly not official forecasts or investment advice. They serve to test assumptions and stimulate discussion. Historically, some of these "unlikely" ideas have turned out to be surprisingly accurate, such as early signs of volatility shocks, the strong gold rally in 2022, the explosive rise of bitcoin in 2017, and even the idea that Nvidia would become bigger than Apple.

As investors, we always consider multiple scenarios. With that mindset, we also read Saxo's Outrageous Predictions for 2026 with interest:

1) Q-Day is coming early

"A breakthrough in quantum computing breaks modern encryption, causing panic in crypto markets and leading to a flight to safe havens. Gold rises towards USD 10,000, while cybersecurity and defensive assets benefit."

2) The Swift-Kelce effect

"A global cultural effect surrounding a celebrity wedding (Taylor Swift & Travis Kelce) stimulates family formation. An unexpected baby boom drives consumption and economic growth."

3) Calm US midterms

"Midterm elections without political chaos lead to calmer markets and a revaluation of risk assets, with Democrats gaining relative influence."

4) Obesity medication for everyone (and pets)

"GLP-1-like drugs are becoming widely available, which is structurally changing nutrition, healthcare, and consumer behavior. Demand for fast food is falling, while health and lifestyle stocks are gaining ground."

5) The SpaceX IPO

"An IPO with a valuation above USD 1 trillion marks the breakthrough of mature commercial space travel, including serious applications such as data centers in space."

6) The AI CEO

"An AI model is appointed CEO of a Fortune 500 company. Strategic decision-making shifts partly to AI systems; human directors supervise. Efficiency increases, governance changes fundamentally."

7) The gold yuan

"China introduces a partially gold-backed yuan, challenging the dominance of the US dollar and reshaping the monetary system."

8) The trillion-dollar AI cleanup

"Poorly managed AI systems cause large-scale errors and high repair costs. Investments in cybersecurity, compliance, and governance technology are skyrocketing after uncontrolled automation fails on a large scale."

We emphasize that these are not Tresor Capital's market expectations. Saxo's Outrageous Predictions serve primarily as a mental stress test: what if the improbable happens?

We are closely monitoring developments in 2026 and will, of course, keep you informed as soon as the capital markets begin to move toward a truly outrageous scenario.

Time Person of the Year: a sell signal for AI or confirmation of a long-term trend?

Time Magazine named the architects of the AI revolution Person of the Year 2025. The cover features Mark Zuckerberg (Meta), Jensen Huang (Nvidia), Elon Musk (Tesla/SpaceX), Lisa Su (AMD), Dario Amodei (Anthropic), and Fei-Fei Li (Stanford University), among others. Time explicitly refers to social influence, but historically, this recognition often raises the same question among investors: is this a sign of maturity... or rather of a peak?

The magazine has built a reputation for putting icons in the spotlight often at or near the peak of their cycle. Jeff Bezos, for example, was named Person of the Year in 1999, just before the dot-com bubble burst; Amazon's stock lost about 90% of its value in the following years. Andy Grove (Intel) received the honor shortly before the technology crash in the early 2000s. And Elon Musk was named in 2021, after which Tesla fell from around USD 400 to USD 100 per share in 2022. These kinds of patterns are often compared to indicators such as the Skyscraper Index: symbols of excessive optimism that, in hindsight, coincide with a turning point.

At the same time, it is dangerous to draw firm conclusions from this. After all, this is anecdotal evidence, not a statistically robust indicator. Both Amazon and Tesla have created exceptional shareholder value in the longer term, despite significant interim corrections. Time's nomination therefore says more about social visibility than about valuation, cash flows, or future returns.

In fact, if influence remains the criterion, Elon Musk already seems to be a serious contender for Person of the Year 2026. His estimated net worth is currently around USD 480 billion, but with a stake of approximately 40% in SpaceX and a possible IPO at a valuation of around USD 1,500 billion, Musk could even become the first so-called "trillionaire" in 2026.

The key question for investors is therefore not whether AI has become "too popular," but where in the value chain the hype translates into sustainable value creation. The Time cover may point to short-term optimism and possible volatility, but it says little about the long-term trend, which is driven by structural investments in computing power, infrastructure, and productivity.

As is often the case, iconic covers are rarely a buy or sell signal in themselves. At most, they are an invitation to re-examine valuations, expectations, and risks.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Does investing in private equity beat investing in stocks?

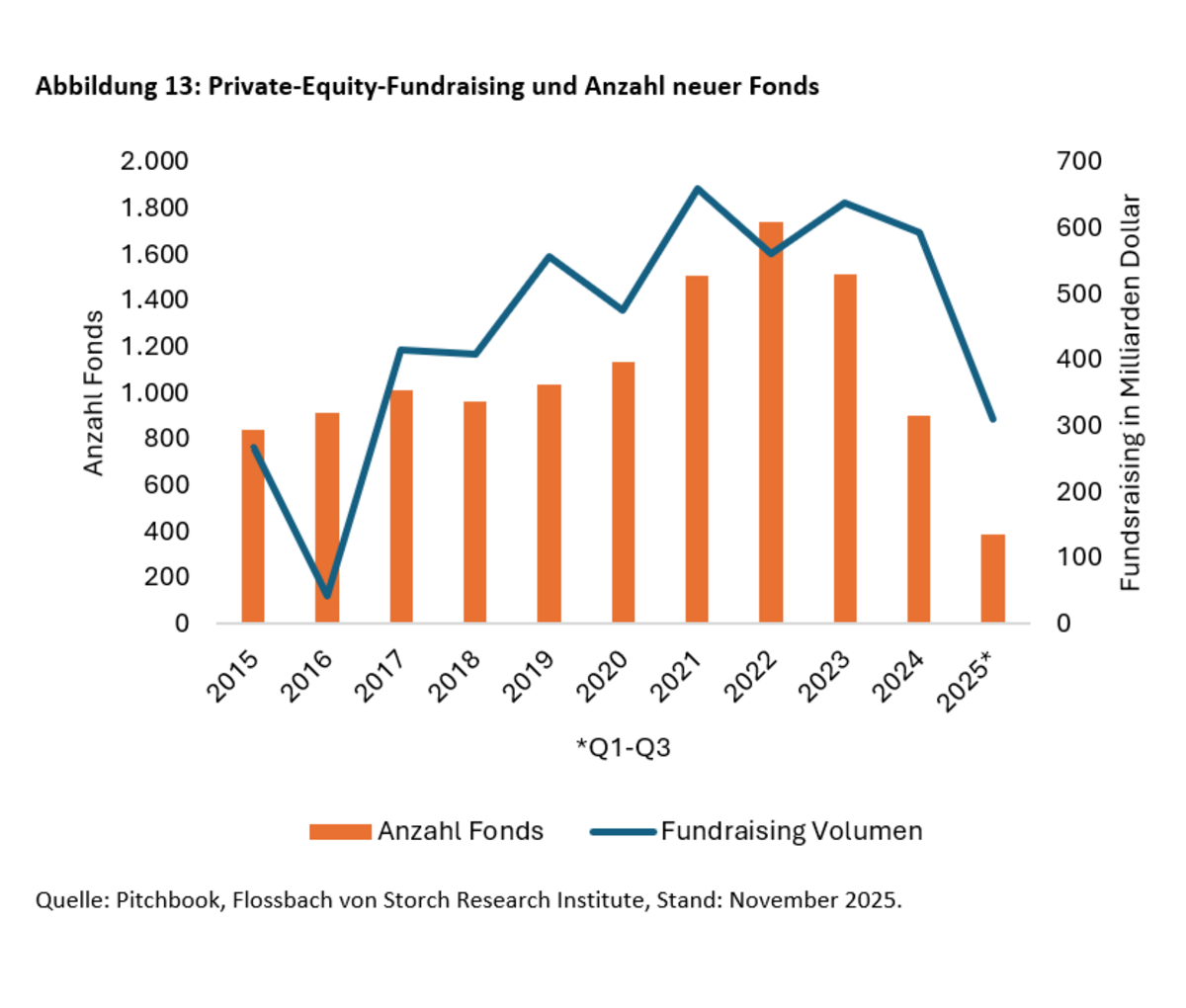

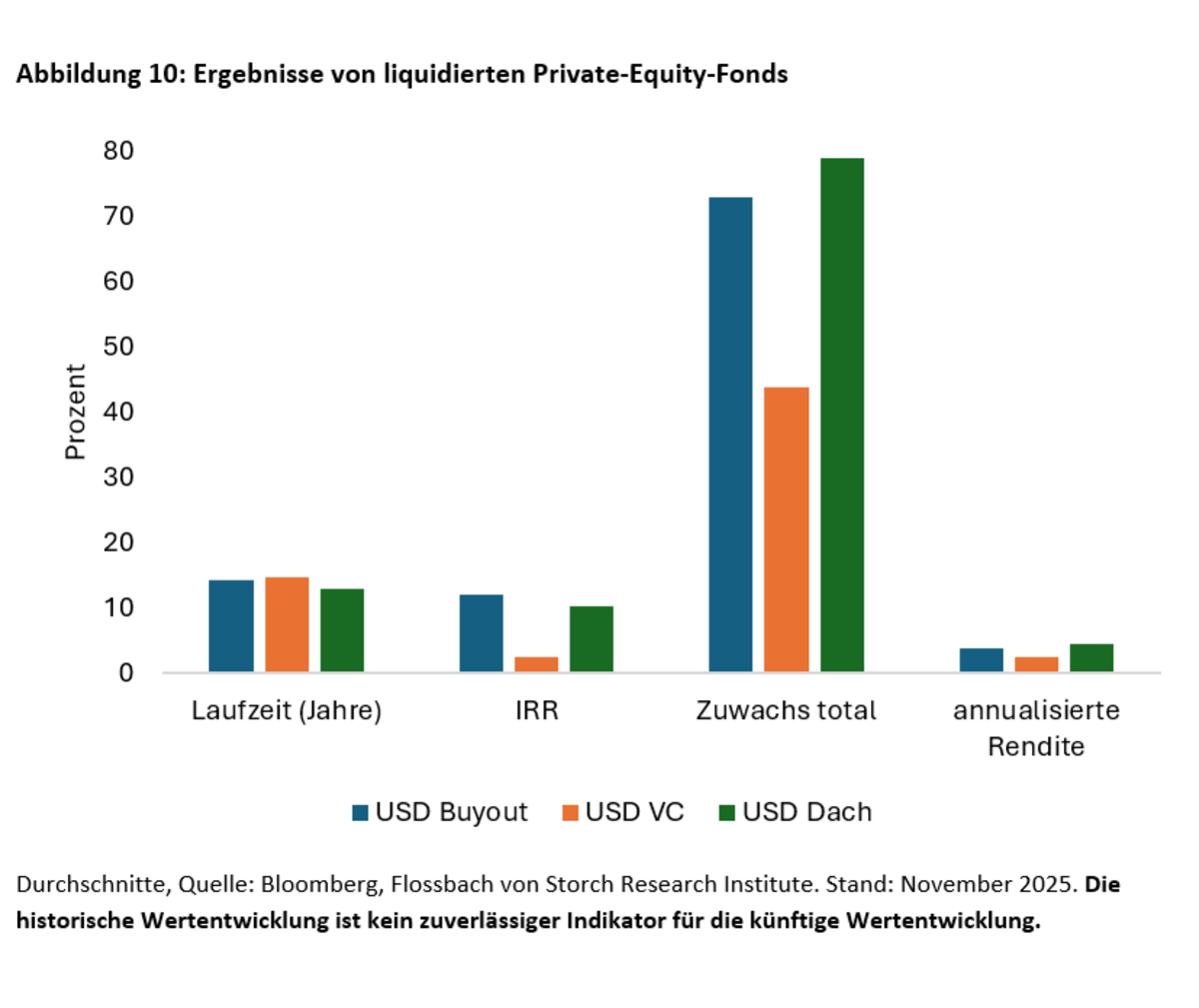

The Flossbach von Storch Research Institute recently published a comprehensive study on whether private equity (PE) structurally outperforms listed equities. The analysis covers 3,752 funds over the period 1999–2023 and is one of the most extensive studies in this field.

To properly interpret the results, the researchers first outline the development of the private equity market and the most important geographical and sectoral shifts.

The size and composition of the private equity market

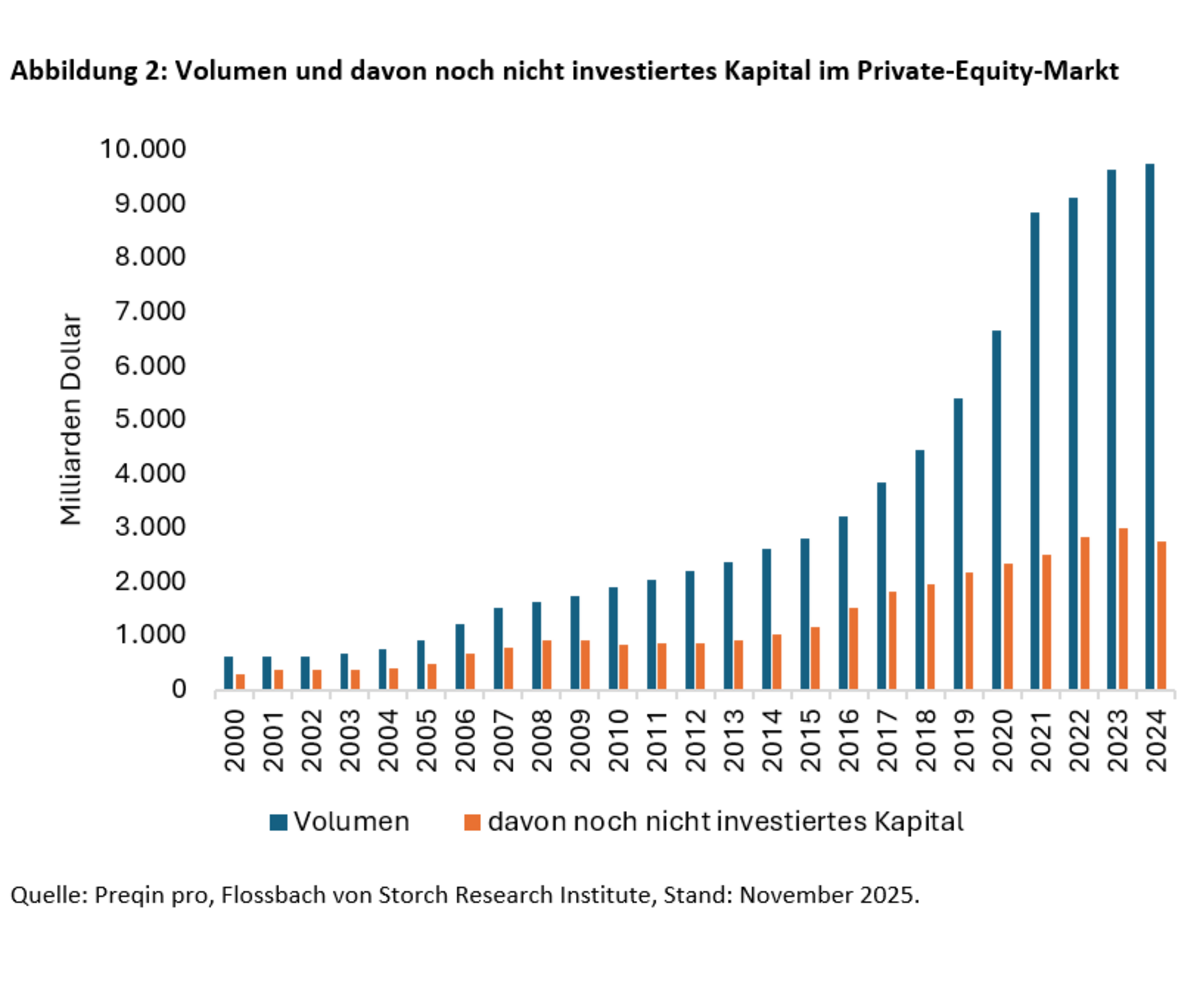

The global private equity market is now worth approximately USD 9.7 trillion, of which around USD 7 trillion has actually been invested. Buyout funds are by far the largest category, accounting for 59%. The remaining 41% is divided roughly equally between growth equity and venture capital.

Geographically, the United States dominates, accounting for 58% of the global PE market. Europe follows with 31%, the lowest share since 2015. According to data from Preqin, US institutional investors allocate an average of approximately 6% of their portfolio to private equity; for foundations, this can be more than 10%. The popularity of PE increased particularly after the financial crisis, in the search for higher returns in an environment of low interest rates.

High return expectations, limited transparency

Private equity is often associated with double-digit annual returns, but the question is whether this expectation is realistic. Transparency about actual returns is limited. Furthermore, returns are usually presented as Internal Rate of Return (IRR) rather than annualized returns, which makes comparisons with stock market returns difficult.

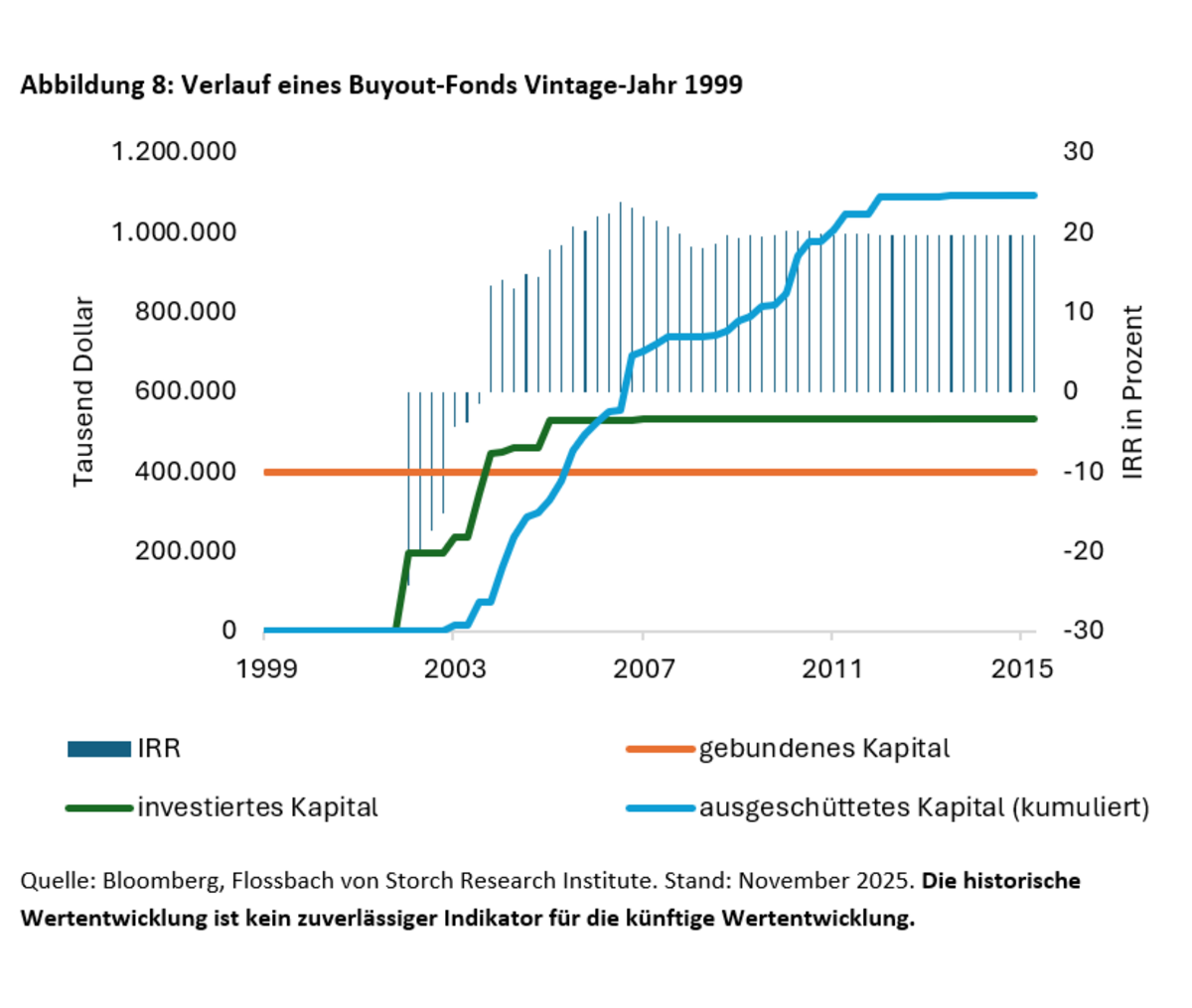

Although fund houses often report IRRs of 10–15%, the study shows that these figures are strongly influenced by the timing of cash flows. For USD buyout funds, the average IRR is 13.3%, while for EUR funds it is 9.4%. However, when looking exclusively at realized cash flows, without assuming reinvestment at the same rate of return, the average annual return is only 3.8%.

In other words, when returns are assessed on a purely comparable basis, private equity does not outperform the stock market on average and in many cases even underperforms significantly. Flossbach illustrates this with a chart comparing the IRR of a typical buyout fund with the actual annualized return achieved. The chart shows that the IRR rises sharply as soon as early distributions are made, while the underlying economic value creation per year hardly increases at all.

The difference is caused by the nature of the IRR measure: it is highly sensitive to the timing of cash flows and implicitly assumes that dividends received can be immediately reinvested at the same high rate of return, an assumption that is rarely realistic in practice.

In addition, there is a very wide spread in returns within each private equity category, which means that averages in themselves are of little explanatory value. International research, including studies by Kaplan, Jenkinson, and Harris, shows that outperformance is indeed possible, but remains highly concentrated in the top 5 to 10 percent of funds and is also highly dependent on the vintage year. For the majority of funds, the returns achieved lag behind those of this leading group.

At the same time, Flossbach acknowledges that private equity can offer investors access to value creation outside the stock market, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises. It is precisely in this segment that operational improvements, professionalization, and restructuring can actually add economic value, an advantage that is less readily available in public markets.

By way of comparison, the S&P 500 achieved an average total return of approximately 7.8 percent per annum over the same period, which means that stock market returns are in practice significantly higher than the net observed returns of private equity. According to the study, this difference can be explained in part by the structural characteristics of the asset class: long-term illiquidity (fund lifespans of ten to twelve years), limited transparency, selection and survivorship bias, and the cumulative impact of costs, including management fees and carried interest, which substantially reduce the ultimate economic return for investors.

Effect of the cost structure

Buyout funds typically use the so-called 2-and-20 structure: approximately 2% annual management fee on the committed or invested capital, supplemented by 20% carried interest above a predetermined hurdle rate, usually around 8%. In practice, according to Preqin, management fees in 2024 averaged around 1.8% for large funds and around 2% for medium-sized funds. Products aimed at private investors are generally more expensive and often have lower hurdle rates.

It is important to note that these costs are not only levied on capital that has actually been invested, but in many cases also on capital that has been committed but not yet drawn down. In addition, valuations of portfolio companies are determined by the fund manager itself, a practice that is regularly identified by regulators as a structural risk to transparency and objective performance measurement.

In addition to fixed and variable management fees, transaction costs, monitoring fees, and advisory fees paid by portfolio companies to the fund manager also reduce the final return for investors. Investors in funds of funds are also faced with multiple layers of costs, further eroding the net return. Private equity funds are closed structures without a regular secondary market and typically have a term of approximately twelve years, with outliers ranging from four to as many as twenty-five years.

Term, leverage, and sources of return

The term of a fund is therefore a crucial determinant of both the effective cost structure and the ultimate net IRR. Liquidity profiles vary greatly between funds, depending on the timing of capital calls and distributions, which makes planning for reinvestment and cash management complex for investors.

The dynamics differ per strategy when it comes to sources of return. Venture capital funds primarily focus on the growth and professionalization of young companies towards an exit, while buyout funds derive their value creation mainly from operational improvements, restructuring, and economies of scale, and to a lesser extent from financial leverage. According to MSCI, the average debt burden in global buyouts over the period 2013–2023 was approximately 1.74 times equity, significantly lower than in the 2000s. Rising interest rates since 2021 have made the use of high leverage structurally less attractive and shifted the emphasis to operational execution as the primary value driver.

Flossbach's conclusion: Private equity does not generally outperform the stock market

Flossbach concludes that it is difficult to substantiate that private equity as an asset class structurally outperforms listed equities. Only under specific conditions can private equity play a valuable complementary role within a well-diversified portfolio. This requires investors to have sufficient illiquidity headroom, careful cash management around capital calls, and access to exceptionally high-quality fund managers.

The analysis shows that it is not the asset class as a whole, but the quality of the fund selection that determines the final return. Outperformance appears to be concentrated in a limited number of top funds, while the average return after costs, illiquidity, and timing effects is often disappointing.

For these reasons, at Tresor Capital we focus primarily on investments in listed private equity asset managers, where scale, transparency, and capital discipline are structurally more visible. Only in exceptional cases, when a private equity fund demonstrably distinguishes itself with a consistent, reproducible, and sustainable track record, do we include a direct fund allocation in our selection and present it to our clients.

What happened this week?

FED further eases monetary policy

As widely expected, the US Federal Reserve (FED) lowered its policy rate by 0.25% this week. However, more important for the markets was the additional announcement that the FED is expanding its balance sheet again by purchasing USD 40 billion in short-term government bonds. This will pump extra liquidity into the financial system via quantitative easing (QE).

Historically, this has supported capital markets: lower financing costs and greater liquidity typically lead to higher valuations of risk-bearing assets, including equities.

AI: strong figures, but growth less certain

The technology sector reported mixed news. AI-related companies such as Oracle and Broadcom reported strong quarterly figures, but at the same time tempered expectations for the period after 2025. They pointed to more limited visibility of future growth and potentially more volatile investment cycles among customers.

This fuels the broader discussion among investors about whether there is an AI bubble. Sentiment surrounding Nasdaq stocks in particular has deteriorated noticeably in recent months, despite the fact that short-term earnings growth remains robust.

In this context, Howard Marks' recent publication "Is it a Bubble?" is particularly relevant. Marks concludes that there is undeniably exuberance, but that no one can say with certainty whether it is irrational, precisely because of the enormous uncertainty surrounding technological breakthroughs. He refers to Mark Twain's adage "History rhymes" and draws parallels with previous technological waves such as railways, cars, radio, and aviation: it was not the technology, but the ultimate winners that were difficult to predict at the time.

At the same time, Marks nuances the comparison with the dotcom bubble. AI is already being applied on a large scale and many leading players are generating substantial cash flows. His main concern is the increasing use of leverage and off-balance structures to finance data centers and chips. In the event of overcapacity, technological obsolescence, or disappointing demand, debt can magnify losses. His practical advice: don't go all-in, but don't go all-out either; diversification within the theme remains crucial.

Transatlantic tensions are rising

Finally, tensions between the US and Europe continued to rise. This week, Donald Trump once again expressed his extreme criticism of Europe's economic, military, and geopolitical position. It seems that Trump is also a loyal reader of our newsletter 😉. After all, we have been critically pointing out for some time that Europe is structurally weakening itself economically with a number of policy choices.

The recently published US National Security Strategy paints a bleak picture: whereas in 2008 the European Union was economically larger than the United States, EU GDP now amounts to only about 65% of US GDP.

Underlying this harsh rhetoric is primarily American frustration about the lack of European unity, including on the issue of enforcing a ceasefire in Ukraine. This fits in with a broader strategic reorientation of the US towards Asia, with China as its primary rival and Russia possibly as a tactical counterpart. Europe, on the other hand, continues to see Russia as the greatest threat.

European leaders reacted with shock and appear determined to take more control of the Ukrainian issue, a development that will remain relevant both geopolitically and economically in the coming months.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Would you like more information about our services? Please feel free to contact us.

Contact us

Disclaimer:

No rights can be derived from this publication. This is a publication of Tresor Capital. Reproduction of this document, or parts thereof, by third parties is only permitted after written permission and with reference to the source, Tresor Capital.

This publication has been prepared by Tresor Capital with the utmost care. The information is intended to be general in nature and does not focus on your individual situation. The information should therefore expressly not be regarded as advice, an offer or proposal to purchase or trade investment products and/or purchase investment services nor as investment advice. The authors, Tresor Capital and/or its employees may hold position in the securities discussed, for their own account or for their clients.

You should carefully consider the risks before you begin investing. The value of your investments may fluctuate. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. You may lose all or part of your investment. Tresor Capital disclaims any liability for any imperfections or inaccuracies. This information is solely indicative and subject to change.

Read the full disclaimer at tresorcapitalnieuws.nl/disclaimer .