Economy & Markets #51 - Europe finances Ukraine, Washington confronts Venezuela

This week's topics:

On the geopolitical front, US involvement in Ukraine is declining, leaving Europe with difficult financing choices. The debate surrounding the use of frozen Russian assets at Euroclear touches on fundamental questions about trust in the global financial system.

The escalation surrounding Venezuela and the lack of a rapid peak in gasoline demand show that energy is once again a geopolitical tool. Fossil fuels remain relevant worldwide, while Europe's energy transition clashes with physical, economic, and geopolitical realities.

Market update – oil price, US CPI, and overly restrictive monetary policy

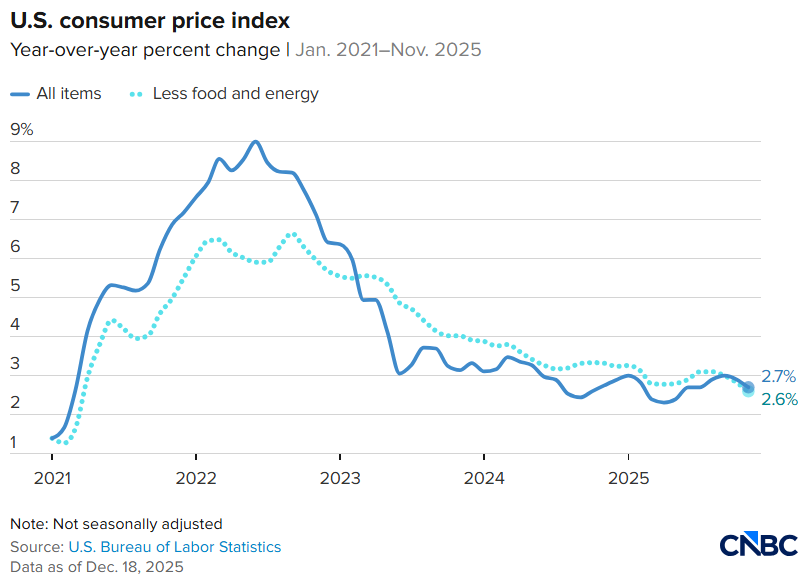

The US consumer price index (CPI) for November 2025, published on Thursday, was significantly lower than expected. Year-on-year inflation came in at 2.7%, compared to a consensus forecast of around 3.1%. Core inflation also continued its downward trend, falling to 2.6%. An important explanation for this further cooling lies in the sharp fall in oil prices. Whereas a year ago a barrel of oil was trading at around USD 85, the price is currently around USD 55 per barrel. Lower energy prices, combined with a limited impact of import tariffs, are now visibly depressing inflation and easing the financial pressure on US consumers.

This development fits in with the broader macroeconomic picture we outlined earlier: a pronounced K-shaped recovery in the United States. Technology-driven and capital-intensive sectors continue to achieve growth and profitability, while a large proportion of households are hardly benefiting from this. For the ‘lower K’, real wages remain largely stagnant, while interest-sensitive parts of the economy, including the housing market, consumer credit and smaller businesses, are clearly cooling down as a result of the continuing restrictive monetary policy.

Against this backdrop, we consider the Federal Reserve's current focus on inflation risks to be too one-sided. With wage growth slowing, partly due to increasing AI adoption, structurally lower energy prices, and a visible decline in credit-driven economic activity, the macroeconomic balance has shifted. In our view, the Fed has sufficient policy space to start easing monetary policy sooner than currently priced in, without losing sight of its inflation target.

Financial markets reacted positively to lower-than-expected inflation figures. Stock markets recovered, long-term US government bond yields fell, and the dollar weakened slightly. Investors are anticipating increased policy space for the Federal Reserve to gradually ease monetary policy in 2026.

At the same time, technology stocks came under pressure earlier this week. The market is taking an increasingly critical view of the financing of the large-scale investments required for AI infrastructure and data centers, particularly when these can no longer be financed entirely from internal cash flows. In this context, the news surrounding Blue Owl Capital received particular attention. Blue Owl is a large US alternative asset manager specializing in private credit and direct financing of capital-intensive projects, including data centers. The company plays a key role in the debt financing of hyperscale infrastructure, especially now that traditional banks are taking a more cautious approach: a development that Jamie Dimon recently characterized with his warning about "the cockroaches in the structured credit market."

According to multiple media reports, Blue Owl has this week halted talks with Oracle about participating in the financing of a large-scale data center project. The project, planned for Michigan, is worth approximately USD 10 billion and is intended to provide AI infrastructure capacity for OpenAI. Blue Owl's withdrawal caused unrest among investors and a sharp reaction in Oracle's share price, and was seen as a sign of increasing caution surrounding capital-intensive technology and infrastructure investments.

Nuance is required here. Both Oracle and Blue Owl have indicated that the reporting may be incomplete or inaccurate. Oracle stated that the project will continue with a different equity partner. Nevertheless, available reports indicate that the initial financing negotiations with Blue Owl have indeed been broken off, which underscores the market's sensitivity to financing risks.

The increasing dependence on more expensive and less liquid capital emphasizes that, particularly within the technology sector, often seen as the primary growth engine of the US economy, the impact of prolonged restrictive financial conditions is becoming increasingly visible. As a result, monetary tightening no longer affects only the interest-sensitive parts of the 'lower K', but is also beginning to have an impact on the capital structure and investment appetite of the leading growth sectors. This has significantly increased the likelihood that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates as early as January.

Euroclear, Ukraine, and frozen Russian assets

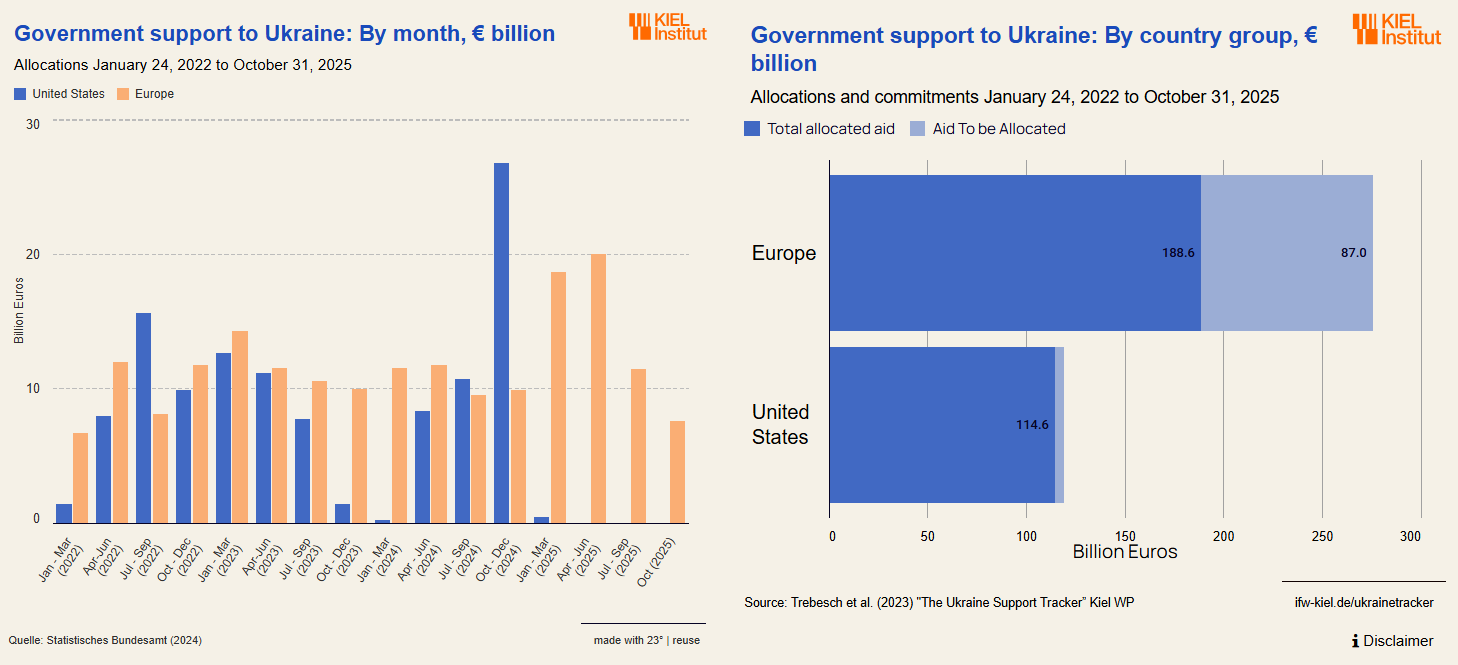

The war in Ukraine has led to an unprecedented deployment of financial and budgetary instruments by Western countries. What was initially presented as temporary emergency aid for a regional conflict has grown into a structural financing commitment of historic proportions. That arrangement is now under increasing pressure.

A key cause is the fundamentally changed attitude of the United States. Whereas Washington under the Biden administration acted as the dominant financier of both military and direct budgetary support, that role has changed abruptly since the change of power. The US willingness to cover long-term deficits in Ukrainian public finances has disappeared. President Trump explicitly positions the conflict as a European problem and shifts the strategic focus to the broader geopolitical balance of power with China. In that context, Russia is seen less as a primary adversary and more as a potential pragmatic player within a changing geopolitical force field.

The consequences of this policy shift are now becoming apparent. According to the Kiel Institute's Ukraine Support Tracker, US contributions have virtually come to a standstill since the beginning of this year. In total, the United States and Europe have jointly provided approximately USD 400 billion in military and economic aid, but that total amount masks a fundamental problem: Ukraine has become structurally dependent on external financing. It is estimated that in the first quarter of 2026 alone, there will be a financing shortfall of approximately USD 135 billion.

For Europe, this means an abrupt redistribution of the burden. European governments and institutions will have to reach agreement on additional financing, while political and budgetary scope is limited. National budgets are under pressure, joint EU debt remains politically sensitive, and there is little willingness to raise taxes or issue substantial new debt. Germany, in particular, continues to oppose joint bond issuance, fearing precedents for debt mutualization.

Against this backdrop, attention has shifted to Euroclear in Belgium, where an estimated €210 billion in Russian central bank reserves are held. These assets have been frozen but not legally confiscated: Russia remains the formal owner but has no power of disposal. The key question is how Europe can make economic use of these assets without crossing the legal line of actual expropriation. Current plans therefore focus on using the interest income as the underlying cash flow for a multi-year loan to Ukraine.

The United States has explicitly taken a cautious stance on confiscation. The fear is that expropriating sovereign central bank reserves sets a dangerous precedent and structurally undermines confidence in the dollar and, more broadly, the global reserve system. This caution is historically understandable. Previous precedents are only marginally comparable. After World War II, German assets were used for reparations, but only after formal military defeat and as laid down in peace treaties. In later cases, such as Iran (1979), Libya (2011), and Afghanistan (2021), these were states with disputed legitimacy or bilateral and humanitarian arrangements.

What makes the current situation exceptional is the combination of factors: these are assets belonging to a functioning and internationally recognized central bank, held at the heart of the global financial system, which are being considered for structural financing of a third country during an ongoing conflict. Central bank reserves are traditionally regarded as the ultimate anchor of monetary security. Once their inviolability becomes politically conditional, the perception of reserve currencies, clearing and settlement infrastructure, and ultimately security of ownership under sanctions regimes changes.

This explains why not only Russia, but also third countries with significant reserves are closely monitoring these developments and reconsidering their allocation decisions. The discussion surrounding Euroclear is therefore more than just a budgetary stopgap solution; it is a stress test for the European financial and institutional architecture and a litmus test for the ambition to position the euro as a global reserve currency. While the United States seems keenly aware of this precedent, several European government leaders are conspicuously lacking this awareness. Seen in this light, the continued rise in the price of gold relative to both the euro and the dollar is no coincidence, but a sign of increasing caution regarding the political conditioning of monetary reserves.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Trump shifts the geopolitical agenda to South America

A recent document on Strategic Security made it clear last week that the United States is further realigning its geopolitical priorities. Attention is shifting away from Europe and focusing more explicitly on its own sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere. This reorientation is in line with a long historical tradition. As early as 1823, President James Monroe stated that the United States would not interfere in European affairs as long as European powers refrained from interfering in the Americas.

The recent escalation of the US policy toward Venezuela must also be viewed against this backdrop. The United States has been striving for years to bring about a policy change in Caracas, driven by a combination of strategic, ideological, and economic motives. This involves reducing Chinese and Russian influence in Latin America, regaining access to the world's largest proven oil reserves, and ending a hostile, authoritarian regime within the immediate US sphere of influence.

Pressure on Venezuela has been further increased in recent times through tougher sanctions and operational measures. These include actively obstructing sanctioned oil shipments and effectively blocking tankers carrying Venezuelan state oil. The seizure of an oil tanker led to a brief rise in both Brent and WTI prices. Although Venezuela currently accounts for only about 1% of global oil production, disruption of marginal volumes in a relatively tight oil market can cause disproportionate price effects.

The underlying structural situation in Venezuela underscores this vulnerability. The country has an estimated 303 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, but in 2025 it will only produce around 900,000 to 950,000 barrels per day, compared to more than 3 million barrels per day at the beginning of this century. Decades of underinvestment, sanctions, institutional decay, and mismanagement at state oil company PDVSA, combined with limited access for foreign oil companies, have severely eroded production capacity.

However, the geopolitical dimension extends beyond the bilateral relationship between Washington and Caracas. China purchases an estimated 80% of Venezuela's oil exports, largely through oil-for-loans arrangements, and has implicitly confirmed its political support for the regime. Russia may reconsider its involvement in Venezuela in the context of broader negotiations on Ukraine, although the outcome remains uncertain.

For the oil market, this implies an asymmetric risk profile. In the short term, upside risks to oil prices prevail due to geopolitical disruptions and limited spare capacity. In the longer term, a political breakthrough in Venezuela could exert downward pressure once sanctions are eased and international investment returns. Some analysts believe that a recovery to around 2 million barrels per day is feasible within a few years, although this will require significant capital inflows and institutional reforms.

Gasoline demand peaks later than expected

The focus on countries such as Russia and Venezuela raises a logical question for many investors. Were fossil fuel investments not on their way to becoming economically worthless? For years, it was assumed that global gasoline demand would peak around 2019 and that investments in oil and gas production would become economically obsolete within five to ten years, driven by electrification and ambitious climate policy. That assumption is proving increasingly untenable.

Recent data and analyses, cited in a Bloomberg opinion piece, among other places, indicate that a structural peak in global gasoline demand is more likely to occur around 2030 to 2035 than previously assumed. After the pandemic, gasoline consumption recovered more strongly than expected. Not so much in Europe or the United States, but mainly in emerging and developing countries where mobility is still in an early growth phase. In large parts of Africa, Latin America, and Asia, demand for transportation and energy is growing exponentially, causing a structural shift in the center of gravity of energy demand.

This also changes the perspective on the energy transition. The relevant question is increasingly less about what transition Europe is pursuing, but rather what transition is actually taking place in countries such as Nigeria, India, Indonesia, and Brazil. The average GDP per capita in many of these economies is below USD 10,000. At the same time, institutions such as McKinsey, Bank of America, and the EIA estimate that complete decarbonization through electrification will cost approximately USD 5,000 per person per year for several decades. This tension limits the speed at which fossil fuels can be phased out globally.

In many emerging markets, the energy transition will therefore not primarily consist of "decarbonization by electrification," but rather substitution: replacing coal with gas and oil. For the time being, the vehicle fleet will also continue to consist largely of combustion engines. European second-hand cars with combustion engines will therefore not disappear, but will find their way to markets such as Lagos, Lahore, or Caracas.

The transition is also visibly slowing down in Europe itself. Major car manufacturers are recalibrating their strategies. Ford has postponed or canceled several EV programs due to disappointing demand and high costs. In addition, the previously announced ban on new cars with combustion engines in 2035 is being watered down, with more room for hybrids and alternative fuels. Reality is forcing pragmatism.

The paradoxical consequence is that, despite sustained or even rising demand for oil, the price of oil may come under downward pressure in the longer term. Both Russian and Venezuelan oil and gas may re-enter the global markets at some point, more than offsetting the growth in demand. Lower prices will then extend the economic life of fossil assets, pushing back the moment of "peak oil" further and further.

This raises fundamental questions for investors. What do structurally high energy costs mean for the competitiveness of renewables compared to fossil fuels? How does the European phase-out of fossil fuels compare to the United States and emerging markets, which are actually focusing on increasing production? And what choices will China make, given that it is still heavily dependent on coal and oil?

There is an additional factor to consider, namely AI. It is expected that by 2028, electricity demand from AI applications will be comparable to France's current consumption, and by 2030, it will be comparable to that of the United Kingdom, Germany, and France combined. In light of this, the question arises as to whether Europe can even keep up in the AI race, given that it is already difficult to connect new businesses and homes to the electricity grid and that electricity prices in Europe are four times higher than in the US and even seven times higher than in China. Positioning for a world in which demand for electrification is growing faster than available production capacity will therefore be one of the key investment questions of the coming decade.

Are offshore wind farms at risk of being structurally overestimated?

Anyone familiar with the lectures and publications of Vaclav Smil and Hans-Werner Sinn will not be surprised by a recent article by Follow The Money. Between 2015 and 2022, both thinkers repeatedly pointed out the same structural weaknesses in European energy policy: the energy transition in countries such as Denmark, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Belgium is primarily driven by political objectives, while physical, technical, and economic constraints are structurally underestimated. What was often dismissed by policymakers at the time as pessimism or a lack of ambition is now gaining broader scientific support.

Smil: energy transitions are slow, capital-intensive, and physically constrained

Vaclav Smil, internationally recognized energy and systems thinker and advisor to Bill Gates, among others, has been emphasizing for decades that large-scale energy transitions are historically slow, extremely capital-intensive, and complex. Modern economies run on reliable, energy-dense, and continuously available energy sources. Replacing them with weather-dependent alternatives is not purely a technological exercise, but a fundamental system change with far-reaching consequences for infrastructure, costs, and security of supply. Smil warns that this systemic dimension is structurally underestimated in policy.

Sinn: rising system costs and distorted market incentives

Hans-Werner Sinn, former president of the German ifo Institute, approaches the same issue from an economic theory perspective. He argues that the Energiewende inevitably leads to rising system costs, distorted market incentives, implicit and permanent subsidies, and a growing dependence on backup capacity. According to Sinn, this will ultimately undermine the industrial competitiveness of Germany and Europe.

The shared conclusion: a hard upper limit on wind energy

Although Smil and Sinn reason from different disciplines, they arrive at a similar conclusion: wind energy cannot be scaled up indefinitely due to intermittency, grid instability, high transport costs, expensive backup capacity, and frequency fluctuations. Their analyses suggest a realistic upper limit of around 30% of the total electricity mix, unless one is prepared to accept extremely high system costs. Recent large-scale power outages, such as in Spain, illustrate these vulnerabilities.

New physical insights confirm the criticism

The recent article by Follow The Money shows that this criticism no longer comes exclusively from economists and energy system thinkers, but now also explicitly from the technical and physical sciences themselves.

A research team led by Prof. Carlos Simão Ferreira (Delft University of Technology) warns against structural overoptimism surrounding offshore wind energy. Their analysis focuses on fundamental physical limitations that are insufficiently taken into account in policy models. The bottom line: wind energy is not infinitely scalable within a given sea area.

As offshore wind farms become larger and turbines are placed closer together, they block each other's wind. This so-called wake effect reduces the average wind speed within the farm, causing total electricity production to grow at a significantly slower rate than policy plans assume. Adding more turbines therefore does not lead to a proportional increase in yield.

To this end, the researchers introduce the wind farm wind factor, which compares actual achievable production with the theoretical maximum. Whereas policy often calculates with capacity factors of 45–50%, the study shows that realistic values, especially for large-scale rollouts, are closer to 30–35%. At the system level, this translates into tens of percent less available electricity than planned.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Would you like more information about our services? Please feel free to contact us.

Contact us

Disclaimer:

No rights can be derived from this publication. This is a publication of Tresor Capital. Reproduction of this document, or parts thereof, by third parties is only permitted after written permission and with reference to the source, Tresor Capital.

This publication has been prepared by Tresor Capital with the utmost care. The information is intended to be general in nature and does not focus on your individual situation. The information should therefore expressly not be regarded as advice, an offer or proposal to purchase or trade investment products and/or purchase investment services nor as investment advice. The authors, Tresor Capital and/or its employees may hold position in the securities discussed, for their own account or for their clients.

You should carefully consider the risks before you begin investing. The value of your investments may fluctuate. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. You may lose all or part of your investment. Tresor Capital disclaims any liability for any imperfections or inaccuracies. This information is solely indicative and subject to change.

Read the full disclaimer at tresorcapitalnieuws.nl/disclaimer .