Economy & Markets #38 - US interest rate cuts and pressure on European pension funds

This week's topics:

Interest Rate Cut Marks Start of Monetary Policy Loosening in US

This week, the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) cut interest rates by 25 basis points to 4–4.25% during its September meeting. Everything indicates that this marks the beginning of a series of successive cuts. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell indicated in his explanation that this step should be seen as a ‘risk management cut’. Although inflation, at 3%, is actually still too high to cut interest rates, the risks of too tight a monetary policy are increasing. The cut should therefore primarily prevent economic growth and the labor market from coming under pressure.

The official statement and Powell's explanation are widely interpreted as dovish: the policy is now more focused on supporting growth and employment than on reducing inflation. This represents a clear shift from the past nine months, in which concerns about rising prices were central.

Several investment banks point to similarities with 2024, when the Fed also implemented a series of interest rate cuts to avert a recession. The consensus among economists is that two more cuts will follow this year, in October and December, and two additional steps in 2026 towards a neutral policy rate of 3–3.25%.

Dot Plot Shows Division Within Fed

The dot plot is a graph published by the Federal Reserve itself, showing the interest rate expectations of each policymaker on an anonymous basis. Each dot represents one Fed member's estimate of where the policy rate will be at the end of this year and in the coming years. It is therefore not a fixed path, but a glimpse into the thinking of the committee.

There was no broad support this week for a 0.5% cut. The median expectation points to three interest rate cuts in 2025, more than the market had priced in beforehand. Noteworthy is the new voice on the committee: Stephen Miran, a confidant of Trump and sworn in as a Fed member since September 16. He advocates for a much more aggressive policy and wants to see interest rates at 2.75% by the end of this year, good for a total cut of 1.75% in 2025, starting with a 0.5% step this week. Interesting detail: there is even a policymaker who would have liked to raise interest rates on Wednesday.

Falling Policy Rates Are Good for the Stock Market

A new phase of interest rate cuts is starting worldwide this week. Because the US dollar is still the world's reserve currency, accounting for approximately 50% of international payments (SWIFT) and involved in 90% of all currency transactions, each interest rate step by the Fed has a large (in)direct effect on lending, currency markets and interest rate cycles. Not surprisingly, other central banks are following suit: the Bank of Canada lowered its rate by 0.25 percentage point to 2.5%, Hong Kong went down 0.25% to 4.5% and Norway took a similar step to 4.0%.

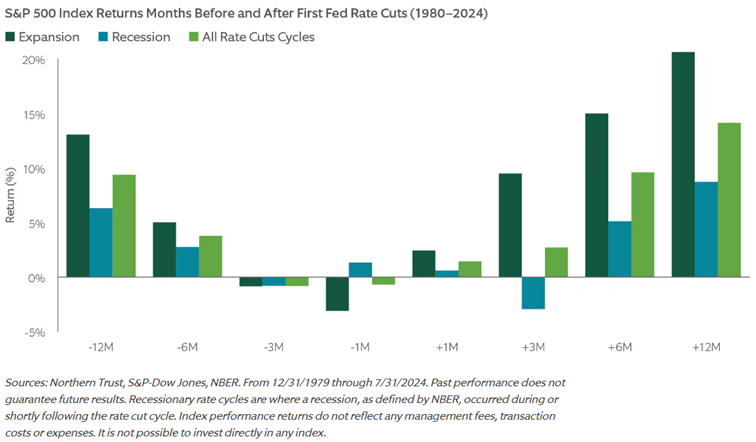

Asset manager Northern Trust investigated in “How stocks historically performed during Fed rate cut cycles” how the S&P 500 has behaved since 1980 after interest rate cuts. The conclusion: stocks rise an average of 14% in the 12 months after the start of a rate cut cycle. Important here is the distinction between scenarios of growth and recession:

- Growth Scenarios – When the economy is still growing (as it is now, with expected US GDP growth of 1.6% in 2025 and inflation around 2.5–3%), stocks often show strong returns of up to 20% after an interest rate cut.

- Recession Scenarios – If interest rate cuts take place during a recession, the prospects are much weaker. On average, the return since 1980 in these cases was still +14.1%, but significantly less stable.

- Volatility – In the first three to six months after a cut, volatility usually increases, after which markets usually start a strong recovery.

- Factor Performance – Factors such as quality, value, momentum and low-volatility perform positively on average after interest rate cuts, with quality showing the most consistent results.

The US economy is expected to grow by approximately 1.6% this year, while inflation remains around 2.5-3%. The crucial difference for the current cycle is that the Fed is not cutting interest rates due to recessionary pressure, but in an environment of moderate growth and declining inflation. In addition, the cuts are supported by fiscal stimulus: higher government spending, substantial investments in infrastructure and energy, and targeted support for consumers and businesses.

This creates a unique climate in which equities benefit from both lower financing costs and a healthy economic foundation. Combined with historical data from Northern Trust (noting that past performance is no guarantee of future results), the outlook for US equities is currently positive.

The Power of the Credit Impulse

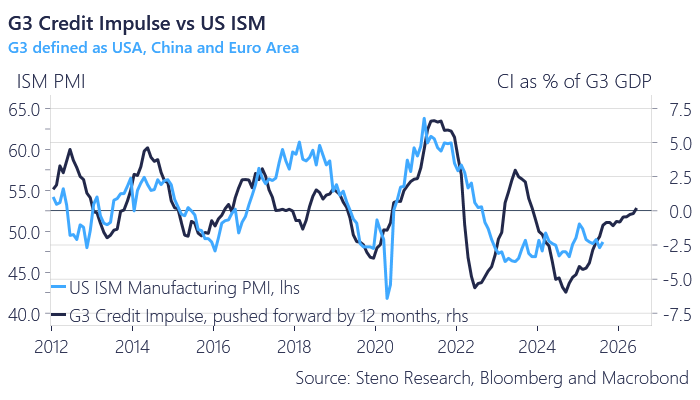

The credit impulse, introduced in the early 2000s by economists Patrick Arthus (Natixis) and Michael Biggs (then at Deutsche Bank), is considered an important leading indicator for both economic growth and capital markets. Arthus demonstrated that whenever China opened the credit tap to stimulate the economy, global equities strongly outperformed in the following months.

The credit impulse looks beyond just bank loans and encompasses total money creation in the economy. Arthus also concluded that monetary easing, via interest rate cuts, quantitative easing (QE), or other liquidity injections, becomes less effective as government debt rises. Additional liquidity then reaches the real economy less quickly and more often flows towards financial markets or alternative assets such as art, luxury goods, or cryptocurrencies.

Biggs also emphasized that changes in credit growth (relative to GDP) are highly predictive: if the credit tap opens, a stock market recovery usually follows. This proved crucial after the 2008 financial crisis and again in 2020, when global credit stimulus during the COVID-19 crisis led to a strong stock market rally, albeit with inflation peaks as central banks intervened too late.

The low real interest rate is therefore no coincidence, but the result of structurally weak fundamentals and high government debt. As early as 2010, Reinhart and Rogoff concluded in "Growth in a Time of Debt" that countries with debt above 90% of GDP structurally experience lower growth and find it difficult to escape the debt trap. Because nominal growth often falls short of interest expenses, central banks are implicitly forced to keep interest rates artificially low.

This explains why investors in Europe, such as the pension funds mentioned earlier, continue to struggle with low bond yields. And why wealth accumulation in this interest rate climate is increasingly under pressure, a theme that was also emphatically highlighted in the Dutch context via Budget Day (Prinsjesdag).

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Budget Day (Prinsjesdag): Increased Pressure on Wealth Accumulation

In the Netherlands, investors are also feeling the effects of this interest rate climate. During Budget Day, it became clear that the tax burden on wealth will further increase. As of 2026, the fixed return in box 3 will increase from 6.00% to 7.78%, which, at a rate of 36%, amounts to an effective levy of approximately 2.8%.

For savers, bond investors, and property owners with low rental income, this means that the tax burden may be higher than the realized return. The pressure is therefore increasing to take more risk and switch to equities or alternative investments to achieve the required return.

The low real interest rate climate in Europe is therefore not a temporary phenomenon, but the result of structural weaknesses, high debts, and lagging investments. While the US and China are accelerating in technology and growth, Europe remains dependent on low financing costs to keep the economy running. For investors, this means an environment in which bonds offer less and less protection, and the search for yield forces other choices.

Low Real Interest Rates Pressure Pension Funds

For institutional investors, it remains challenging to achieve returns in an environment of low or even negative real interest rates. Major Dutch pension funds such as ABP (-3.7%) and PFZW (-4.8%) already reported negative returns earlier this year. In Belgium, 150 pension funds managed to realize an average return of only +0.3% over the first six months.

The difference in performance lies mainly in the investment strategy: Dutch funds value liabilities at the current interest rate and therefore buy many long-term bonds as a hedge, which makes them extra sensitive to interest rate movements. Belgian funds are more invested in short-term paper, which limited losses this year. But the broader problem remains: bonds at low real interest rates hardly provide any purchasing power preservation.

Why Does the Real Interest Rate Remain So Low?

For bond investors, the low or negative real interest rate (the nominal interest rate minus inflation) is extremely unfavorable because future purchasing power is not sufficiently protected. The question arises: why does the ECB keep the real interest rate in Europe so low, often even negative?

Interest essentially functions as a steering instrument: it determines the incentive to consume now or to save and spend later. Yet there is increasing criticism that central banks are keeping interest rates low primarily to help governments finance their high debts. According to economic theory, the real interest rate is determined by factors such as structural growth, and that growth in turn depends on the development of the labor force, the number of hours worked, and labor productivity. On top of that comes a premium for expected inflation, which together forms the nominal interest rate.

The problem is that many of those sources of growth are drying up in Europe. The labor force is shrinking, productivity growth is stagnating, and high energy costs, absenteeism, many vacation days, and heavy regulatory pressure are shifting jobs to the US and China. This is further eroding the foundation for structural growth. Mario Draghi warned again this week about this trend:

"Our growth model is crumbling. Vulnerabilities are increasing... and we have been painfully reminded that inaction not only threatens our competitiveness but also our sovereignty itself."

"Too often, excuses are made for this slowness. We say that it is simply how the EU is structured. Sometimes inertia is even presented as respect for the rule of law. That is complacency."

According to Draghi, former ECB president and appointed by the European Commission to write a reform plan, the EU risks falling permanently behind. Only a fraction of his previously presented 383 recommendations have been adopted. The biggest pain points: high energy prices, slow regulation, and insufficient investment. Especially in the field of digital technology and artificial intelligence, Europe lags far behind the US and China, which are investing billions and implementing applications on a large scale. This puts pressure on both the technological sovereignty and the long-term growth potential of the Union.

Today, the credit impulse is still widely used as a temperature gauge for the markets, including by Steno Research. Their analyses show that the indicator has recently turned from restrictive to expansive. With the start of interest rate cuts in the US, Europe, and China, and proposals to ease bank reserves, more liquidity is re-entering the system. This points to an upcoming revival in industrial activity, and ultimately also in the capital markets.

Receive weekly insights in your inbox

Exclusive analyses and updates on family holdings and global market developments.

Would you like more information about our services? Please feel free to contact us.

Contact us

Disclaimer:

No rights can be derived from this publication. This is a publication of Tresor Capital. Reproduction of this document, or parts thereof, by third parties is only permitted after written permission and with reference to the source, Tresor Capital.

This publication has been prepared by Tresor Capital with the utmost care. The information is intended to be general in nature and does not focus on your individual situation. The information should therefore expressly not be regarded as advice, an offer or proposal to purchase or trade investment products and/or purchase investment services nor as investment advice. The authors, Tresor Capital and/or its employees may hold position in the securities discussed, for their own account or for their clients.

You should carefully consider the risks before you begin investing. The value of your investments may fluctuate. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. You may lose all or part of your investment. Tresor Capital disclaims any liability for any imperfections or inaccuracies. This information is solely indicative and subject to change.

Read the full disclaimer at tresorcapitalnieuws.nl/disclaimer .